|

|

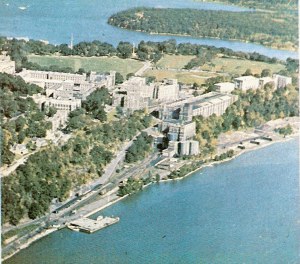

New York - Topography

Economically and socially significant is the fact that New York is the only State touching both the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. The State's boundaries, established by natural waterways, treaties, and interstate arbitration, suggest in outline an early twentieth-century box-toed shoe, slightly dented as it boots Lake Erie, while Long Island trails like a loose spur from its worn heel into the Atlantic. About 550 miles of the State boundary is on land; somewhat more than that amount along or in water. The 47,654 square miles of land and water within these boundaries comprise a large variety of topographic forms. Economically and socially significant is the fact that New York is the only State touching both the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. The State's boundaries, established by natural waterways, treaties, and interstate arbitration, suggest in outline an early twentieth-century box-toed shoe, slightly dented as it boots Lake Erie, while Long Island trails like a loose spur from its worn heel into the Atlantic. About 550 miles of the State boundary is on land; somewhat more than that amount along or in water. The 47,654 square miles of land and water within these boundaries comprise a large variety of topographic forms. The Adirondack Mountains, occupying the northern lobe, are made up of a great mass of rocks, which, by virtue of their superior resistance to erosion, tend to retain their altitude. They are mountains in the sense of their greater height rather than in the sense of being formed of folded structures. Drainage sought out geologic faults and formed valleys. At the close of the Ice Age, dams of glacial debris were left at the southern extremities of the valleys, streams were backed up, and the many lakes of the Adirondacks were formed on north-northeast to south-southwest axes.

The loftiest mountains lie about 25 miles west of Lake Champlain. From them elevations decrease gradually in every direction. On the cast they terminate abruptly at Lake Champlain; on the south and north they run out in fingerlike ridges; on the west they end in a peneplain with only minor hills. On the northwest the Adirondack rocks form a low ridge which cuts through northern Jefferson County and crosses the St.Lawrence River, in which it forms the Thousand Islands.

The Allegheny Plateau, largest single physiographic province of New York, covers almost the entire southern part of the State. Its fairly uniform altitude of about 1,600 feet is cut by valleys some 500 feet deep. At its eastern margin it rises to the 4,000-foot altitude of the Catskill Mountains. At the northeastern corner of the plateau, massive limestone strata form a cliff known as the Helderberg Mountains. The sedimentary rocks of the plateau are inclined gently away from the northern oldlands. The drainage has a tendency to follow the dip-slope, so that the major streams of the area flow generally south.

The Catskill Mountains, like the Adirondacks, are not mountains in the sense of being composed of folded structures. Their separate peaks are lofty ground between the valleys of a deeply dissected plateau. As the streams that drain the area tend to form straight valleys through the plateau, the mountain peaks have a tendency to form more or less continuous ranges. Lakes are few and small; the only large bodies of water are Ashokan and Schoharic Reservoirs, both man-made.

The Finger Lakes lie in north-south valleys in central New York. Geoloaists believe that the lake valleys once contained southward-flowing rivers which were backed up by dams of glacial debris formed during the Ice Age, and that the new or post-glacial drainage was forced to seek the northward course it now takes. The sides of the valleys rise abruptly to the broad back of the Allegheny Plateau. Tributary streams, tumbling down the steep slopes, have cut glens and produced many waterfalls. Taughannock Falls near the head of Cayuga Lake plunges 215 feet, the highest waterfall east of the Rockies.

The Lake Ontario Plain extends 160 miles east and west along Lake Ontario, and reaches southward 30 to 40 miles. An extension of it forms a bench five miles wide along the shore of Lake Erie, southwest of Buffalo. The plain is a low-lying surface with an ill-defined drainage system giving rise to numerous swamps. Projecting 50 to 150 feet above the general level of the plain are glacial deposits; many of which stand like islands in swampy bottoms. These deposits are of two types: those dumped by the moving ice (drumlins), and those formed in temporary lakes during the Ice Age (kames). In the vicinity of Syracuse and Lyons, drumlins are numerous enough to give the plain a rolling and hilly appearance. In the vicinity of Rochester, kames predominate. Running east-west through the western part of the Lake Ontario Plain, the Ridge, an outcropping edge of the massive Niagara limestone, extends to the Niagara River and produces the waterfall. As the limestone ledge is undermined, its edge breaks off, the falls migrate upstream towards Lake Erie, and the deep Niagara gorge is lengthened approximately one foot a year.

The St.Lawrence Valley is a narrow inner-lowland north of the Adirondacks. About 18 miles wide and reaching northeast from the Thousand Islands to the Canadian boundary and then east to Lake Champlain, it has a mean altitude of about 300 feet. At its southern boundary, ground moraines of glacial sand have leveled off the terrain by filling the small valleys of the Adirondack foothills.

Between the Adirondacks and Lake Ontario is the Tug Hill Plateau, a cuesta separated from the Adirondack oldland by the narrow Black River inner-lowland, above which it rises 1,700 feet. Somewhat of a wilderness, the plateau is unfertile and is not traversed by State roads.

The Mohawk Valley is an inner-lowland between the Adirondack oldland and the Allegheny Plateau. Its head is near Rome, which stands on a narrow divide separating the drainages of the Ontario Plain, the Black River, and the Mohawk River. At Little Falls and at Sprakers, upthrust blocks of the ancient Adirondack rocks reach across the valley and form high spurs, or 'noses,' on both sides of the river. Between Sprakers and Schenectady the valley cuts into layers of limestone, forming rather high banks. East of Schenectady the valley widens out into a plain formed by a glacial lake.

The Hudson-Champlain Valley runs north and south across the State. Wood Creek, which flows into the long, narrow, southern end of Lake Champlain, is separated at its source from a tributary of the Hudson by a divide less than 20 feet high and half a mile wide.

From its source to Hudson Falls, the Hudson River is a typical Adirondack radial stream, making abrupt bends to conform to the system of faults. At Hudson Falls it enters the Hudson-Champlain Valley and flows south through a belt of shale. Below the confluence of the Mohawk it becomes an estuary, so that tides are felt 150 miles up from its mouth. Near New York City it enters the chasm it cut in its early development through the Highlands, south of which the Palisades form its precipitous west bank. West of the lower Hudson, the Shawangunks form a mountain range 2,000 feet above the Rondout-Neversink and Walkill Valleys.

South of Lake Champlain the region east of the Hudson River is occupied by the Taconic Range and its western foothills. The present summits are not the actual crests of the original upfolds, but rather the heights between valleys etched in the softer or more soluble rocks. The mountains, locally known as the Berkshires, extend across the New England line and are terminated on the south by the Highlands of the Hudson.

Long Island is an expanse of flat land underlaid by sand and gravel of the glacial period. This great glacial terminal moraine rests on a cuesta of relatively recent Coastal Plain sedimentary rocks, which faces the New England oldland across the sea-invaded inner-lowland called Long Island Sound.

In its early development the waterways of New York State formed perhaps its greatest natural advantage. Extending into the most fertile parts of the territory, and into the areas richest in forests and minerals, they opened up the land for settlement and provided water power and arteries of transportation. In timd of war the shores and valleys became the objectives of strategy and the fields of battle.

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.